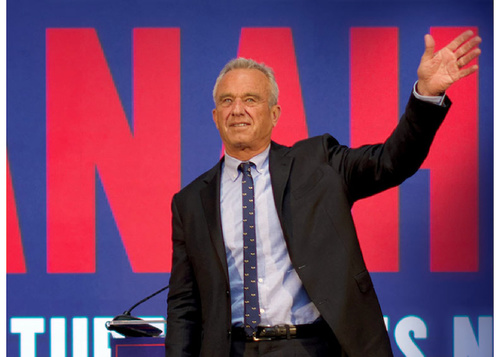

Candace LaForest (above) is charged under the state "super-drunk" law because her blood alcohol level measured 0.27 -- more than three times the legal limit to drive. (Troy Police Department photo)

It was a frigid Friday night as Melinda Weingart, a Troy police officer, approached a black pickup that hit curbs three times before driving onto the snowy median. What she heard next was unexpected.

"Mindy, it's me -- Candace," a woman shouted from behind the wheel of her 2013 Dodge Ram.

"I immediately recognized the pickup driver as Candace LaForest, a felow Troy Police Officer," Weingert records in a three-page case report on the midnight traffic stop Jan. 18.

Her report and 34 other pages of investigative documents were obtained Thursday afternoon by Deadline Detroit in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. They provide a look at a drunk driving arrest that is far from routine and reflect a no-favoritism approach that contrasts with "courtesy rides" home in selected cases by some suburban or small-town police forces during past eras.

"Clearly the 'Code of Silence' is not what it used to be," says John Courie, a Schoolcraft College criminal justice professor asked to comment on the case. "Today's officers are better-educated and better-trained, with greater emphasis on ethical behavior."

Earlier coverage: Officer Candace LaForest of Troy Took a Career-Risking Friday Night Drive, Feb. 7

When Weingart and patrol partner Patrick McWilliams recognized their off-duty suspect, they initiated a process that involved three sergeants, a lieutenant, a captain who came from home and a district court magistrate. Separate accounts by each participant reflect a by-the-book response that started when McWilliams radioed for a supervisor "due to the fact that the driver is a co-worker," as Weingart puts it in the language of policing that hasn't changed since "Dragnet."

Three sergeants, a lieutenant and a captain became involved with the Jan. 18 arrest of Troy Police Office Candace LaForest, 34.

The copspeak may be old school, but the administrative reports show a no-exceptions policy that Weingart signals during her first contact with 34-year-old LaForest, who was a 911 call-taker and police service aide in Troy for three years before becoming an officer in 2005. "I advised her that she appeared to me to be very intoxicated," the officer's case report says. "I then asked her what in the heck she had been thinking."

Captain's Persuasion

After Weingart drove her colleague to police headquarters for processing, Capt. Robert Redmond -- responding around 12:30 a.m. after a lieutenant called his home -- had to coax the sobbing suspect from the patrol car.

"She was curled up against the driver's side door, crying heavily," the captain writes in a two-page report for the file. "She began asking me to 'please just let someone drive me home.' I told her that she was under arrest for drunk driving and that she was going to be treated just like every other citizen that gets arrested.

"She continued begging to be driven home. . . . She said 'I'm drunk, I need help, I have a problem.' She said this several times as she began crying heavily again. She reeked of alcohol and clearly was extremely intoxicated. . . . One last time she asked me, Can't' you please just drive me home?' "

In an apparent attempt to let her body metabolize some of the alcohol, LaForest -- who had refused roadside sobriety checks and a portable breath test -- agreed twice to take a Breathalyzer test and then backed out each time after a legally required 15-minute observation period. Around 2 a.m. that Saturday, Sgt. Nathan Gobler faxed an affidavit to a 52nd District Court magistrate on weekend duty and got a search warrant at 2:52 a.m. to draw two vials of blood.

A paramedic took those samples in an ambulance outside the Troy lockup at 3:38 a.m. -- more than three and a half hours after the eastbound Big Beaver traffic stop.

Even with that lag in measuring her intoxication level, a Jan. 23 report shows the Michigan State Police lab in Lansing measured 0.27 grams of alcohol per 100 milliliters of blood -- more than three times the legal limit of 0.08 to drive. So LaForest, who's on administrative leave, is charged under Michigan "super-drunk" law.

Evening at Sports Bar

At the time, as LaForest told Officer Weingart, she was heading home to Macomb Township from Norm's Field of Dreams, a sports bar and grille on Rochester Road, less than two miles from her arrest. "She advised me she had been there with a friend she knew 'from hockey,' " the case notes say.

Seated in the back of her colleague's patrol car after being frisked (she was unarmed), LaForest "mentioned her recent divorce and told me she was just trying to get through the divorce," writes Weingart, who refers to her co-worker as Candace Rushton, presumably her maiden name.

Evidence in the case includes a "Diet Pepsi bottle with suspected alcohol in it" that was spotted in the Dodge Ram's cup holder when Officer McWilliams drove it to police headquarters. "It appeared to be too light in color to be Diet Pepsi," Weingart dutifully records. "Officer McWilliams opened the bottle and smelled the contents, and it smelled of intoxicants."

LaForest, arraigned last week, is free on $1,000 personal bond. Her case is transferred to Novi District Court because Troy judges know her.

The situation "is very uncomfortable for the officers and civilians who work with her," acknowledges Sgt. Andy Breidenich, the department's public information officer. Troy has about 90 officers and roughly 40 support personnel.

"Culture of Transparency"

During an interview in the headquarters lobby, the community services sergeant also spoke about "a culture of transparency" that meant everyone involved knew "our hands were tied -- we had to do the right thing." His department's official seal includes the words "integrity, professionalism, accountability."

Asked about the time when fellow officers and sometimes departments might shield a colleague's missteps behind a "blue wall of silence," Breidenich said: "The culture has changed in law enforcement as we've become more professional. We're also more visible to the public now with the Internet, social media and in-car cameras.

"We don't want to see one of our own in trouble, and we have concern for her well-being -- that she gets the help she needs. But we've got to be honest. This is Troy -- we're going to do things the right way."

A similar perspective comes from John Courie, a western Wayne County attorney who is a professor at Schoolcraft's Criminal Justice Academy. His experience includes serving as a Macomb County chief assistant prosecutor and Detroit police commander.

"Command officers must reinforce to officers to put loyalty to the badge and the public above loyalty to all else, including misbehaving colleagues," Courie tells Deadline Detroit by email.

"It boils down to the sergeants. They are the ones that will be called to the scene when someone of prominence is pulled over for some infraction. Ranking officers must make it perfectly clear to the sergeants the every such incident must be handled by the book."

Courie, whose students include aspiring officers, contrasted the Troy case with seemingly lenient treatment of Detroit Councilman George Cushingberry when he was stopped Jan. 7 outside a club in that city and released with a ticket despite marijuana odor and an empty rum bottle.

"The officers did what they were supposed to do and called the sergeant," says the educator, whose Detroit career included time in the police internal affairs section. "The sergeant, for whatever reason did not [do the right thing]. The chief of police sent a strong message that if the sergeants don't do their job, they will be disciplined."

by

by