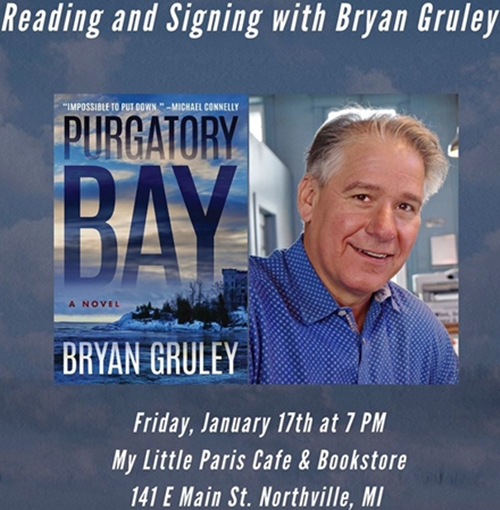

An author with Metro Detroit roots returns this week to promote "Purgatory Bay," a thriller published today.

Bryan Gruley's latest book is set in Michigan, just like his first four novels, and this time involves murder, vengeance and deadly drones.

He'll read from it and sign copies from 7-8:30 p.m. Friday at My Little Paris Café & Bookstore, 141 E. Main St. in Northville. (Event listing.)

"A fiendish quest for revenge drives Gruley’s tense second thriller set in the same region of Michigan as 2018's 'Bleak Harbor,'" says Publisher's Weekly. "Readers with the patience for the antics of maniacal, over-the-top villains will have fun."a

The former Detroit business journalist lives in Chicago and reports for Bloomberg.

Below are the five-page prologue and eight-page first chapter of "Purgatory Bay," originally presented here Dec. 8 as the first online excerpt.

By Bryan Gruley

Prologue

March 18, 2007

“Miss? Your license again, please? Just to reconfirm.”

The Michigan state trooper standing over Jubilee was a rucksack of a man with jowls as pale and greasy as diner pork chops, his eyes tiny bullets buried in his cheekbones. The smudged nameplate on his left breast pocket read Christian.

Jubilee, hungover, throat parched, head pounding, sat in an angle iron chair with too-high arms in the state police post at Lapeer, an hour north of Detroit. She had driven past the post a hundred times, tapping her brakes at the sight of the blue-and-gold cruisers parked outside the low brick building. She had never been inside until one hour and fourteen minutes before.

“Reconfirming what, Officer Christian?” she said.

Christian straightened, looking offended. Who’s he to be offended? Jubilee thought. She had assumed that she was the victim there, although she didn’t know of what because the cops wouldn’t tell her anything.

“Reconfirming your particulars, miss.” His voice was a high-pitched rasp, like when her late grandfather had spoken to her after coming off his ventilator. “I need your driver’s license. We didn’t get a good copy of it the first time. It’s routine procedure.”

They had rousted her from Tessa’s house just after six a.m. All they would say was that she had to get her wallet and come with them immediately. “What is going on? Is something wrong?” Mrs. Fluegel had asked repeatedly, to no avail.

Jubilee had sat uncuffed in the back of the state police cruiser, siren blaring as it raced up M-24, the speedometer creeping toward a hundred miles per hour. She’d felt afraid, not because of the speed but because the air inside the car seemed to have been drained of oxygen, the officers silently, implausibly angry, though they wouldn’t answer her questions, wouldn’t even look at her.

At the post they’d stuck her in a chair with a seat that made her have to keep scooching back and told her to stay put, as if she were still a child, not seventeen years old and a high school senior recruited to play soccer goaltender at Princeton in the fall.

“Why am I here, Officer?” she asked.

“Miss, I’m only going to ask for the license one more time.”

Jubilee felt the cold damp beading on the back of her neck, the nausea spreading in her gut. She wondered if the cops had called her parents, who were at the family cottage up north, a three-hour drive away. Jubilee had stayed home in Clarkston for the weekend. Her mother had warned her not to go to any parties, and of course Jubilee had ignored her.

She started humming, softly so the officer wouldn’t hear. Humming the song that had been playing in her head when Mrs. Fluegel had woken her from drunken sleep, the uniformed officer standing incongruously in the door of Tessa’s bedroom.

All Jubilee could think was, Oh shit, my dad is gonna be pissed. Oh shit. They can’t arrest me for drinking a few Corona Lights—hell, Tessa was doing frigging Jäger bombs with Bobby. Shit, Mom will not be happy . . .

“Miss Rathman,” Christian said. “I need your license, please.”

Jubilee kept humming as she dug in a pocket for the license. She had read that humming could keep you from puking. It seemed to have worked the night before, when she had thought she might barf in Bobby’s half-bath off the kitchen—she might have sneaked a couple of Jäger shots herself—and had started humming along with the song blaring outside the bathroom door. She didn’t know the name of the song or the lyrics, but it had a bouncy chorus that was easy enough to hum. And she had not puked.

“Here,” she said, handing Christian her license. “Please don’t lose it.”

He took the license and started to walk away.

“Hey,” Jubilee said. “Could I at least call my parents?”

Christian turned halfway back and hesitated before answering. “As we said, there’s been a situation.”

“You didn’t say anything about any situation.”

“We’ll let you know when we know.”

The cops had taken her cell phone. She remembered one nonsensical text she’d gotten when the party at Bobby’s parents’ house had just begun to rock, a little after midnight. It was from her younger sister, Kara: 2Ju xkYaf .. 8983a. Jubilee figured she had raided their parents’ liquor cabinet again. Kara never learned.

“Can I just call my parents? They’ll worry.”

The eyelids surrounding Christian’s bullets narrowed. He canted his head, studying her anew. “Tell me, Miss Rathman.” Christian held the license up in front of his face. “Jubilee Magdalena Rathman.” He dropped the hand holding the license. “Magdalena? Is that some sort of Italian thing? Rathman doesn’t sound Italian.”

“Excuse me?”

“You haven’t yet blown into the Breathalyzer this morning, have you, Jubilee Magdalena?”

“I wasn’t driving, Officer.”

“Trooper,” he said, before he walked away.

The room smelled faintly of garlic. Christian crossed the tile floor to an office about twenty feet away. Jubilee felt an urge to walk over and open the door and scream, Tell me what happened, dammit. But she refused to be one of those girls who used hysteria as a crowbar.

She watched the cops in the office: Christian, another man, and a uniformed woman who appeared to be in charge. The door was closed, but Jubilee could see through a window.

Every few minutes another cop would walk past, ignoring her or giving her a sideways glance without really looking at her. She wondered if they’d been ordered not to engage her.

A clock on the wall above the office said it was 7:38. Jubilee’s parents would be awake by now, her mother putting the coffee on. Jubilee wished she had her phone, wondered if they knew where she was, if they had called, why the cops wouldn’t put them through.

In the office, the woman leaned her rump against a desk, hands on her hips, her face a mask of too much makeup glowing in the fluorescent light. A ring as big as a walnut engulfed her wedding finger. Next to her on the desk was a beer mug filled with pencils and pens, a stapler, and a small brass trophy in the shape of a star.

Christian stood at a fax machine a few feet away, pages spewing into his open palms. The other male trooper stood with his back to the window, arms folded, nodding as the woman spoke. Every few seconds, the woman would glance at Jubilee through the window. She looked concerned, though whether the concern was for Jubilee or something else Jubilee couldn’t tell.

The pages kept churning out of the fax—she could just hear the dull click and whir—and Christian scooped them off one at a time, giving each a cursory look before placing them face-down on a stack next to the machine. Then a page appeared to catch his attention. He stopped stacking, his eyebrows edging upward as he studied it. He touched a button on the machine, turned, and walked the page over to the woman.

Jubilee leaned forward in the chair and saw the woman’s eyes widen ever so slightly. She lifted her eyes toward Jubilee.

Jubilee rose from the chair.

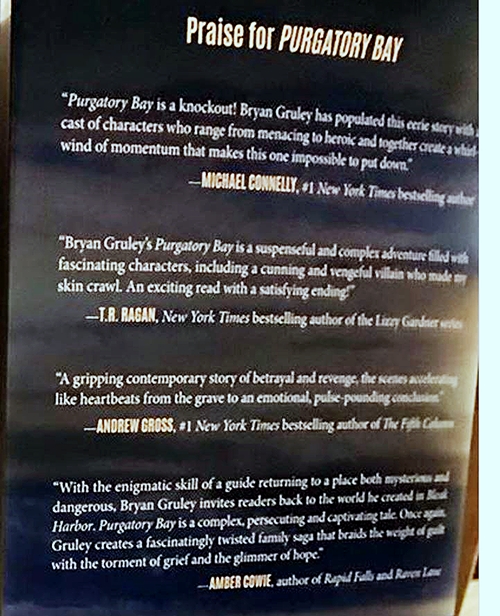

Back cover blurbs

The woman dropped the page and came off the desk, barking something at the cop who wasn’t Christian. He spun toward Jubilee as she shoved the office door open and saw the woman’s nameplate: Sgt. White.

“Miss Rathman,” he said, “you need to go back to your seat.” “What’s going on?” Jubilee addressed herself to White while pointing at the fax. “Show me.”

Christian reached across the desk for the page he’d given the woman. “Here,” he said.

“Christian, no,” the woman said, stretching to grab his arm. She was too late. Christian dangled the black-and-white photograph for Jubilee to see. The picture showed a boy, almost entirely naked, splayed unnaturally on the edge of a pond. Jubilee knew the pond.

“This your brother?” Christian said. “Joshua, right?”

Jubilee felt the burble in her gut again, willed it back down, and without thinking snatched the brass star off the woman’s desk. It was heavy, and one point of the star bored into Jubilee’s palm, though she wouldn’t notice until she was in the ambulance covered in blood, her own and Christian’s.

She lunged at him and snapped the trophy at his face, flinging her forearm out like she would to stop a soccer ball flying at her in the net.

She was going for his nose, but the other male cop deflected her arm as he grabbed her. One of the star’s points spiked Christian’s right eye. He fell back against the fax machine, screaming as Jubilee crashed to the floor beneath the other cop, smelling his breath and sweat and the starch on his uniform, hearing him spit into her ear, “Get down, you little bitch. You’re under arrest.”

Chapter 1

Twelve years later

Thursday, 9:15 p.m.

Ophelia is not answering.

Mikey Deming ends the call, tucks her phone into a cupholder,

decides she’ll go to her sister’s apartment. The lights of downtown Bleak Harbor beckon as Mikey drives the shore road, the familiar bay dark and silent on her right. She checks the dashboard trip meter. She’s made good time.

Maybe Ophelia went to bed and turned her phone off, although she rarely does the latter. Maybe she’s staying with Gary tonight. But Ophelia knows her sister and niece are on their way from Ann Arbor.

Why wouldn’t she expect a call?

Mikey hears the voice of her husband, Craig, in her head: Why don’t you be Michaela and let Ophelia be Ophelia? She glances at Bridget.

Bryan Gruley: "In small towns, you think you know people. You don't." (Photo: Bloomberg)

Their fifteen-year-old is asleep in a jumble of pillow and black fleece, her face hidden while waves of her red hair spill out from under the fleece stitched with a gold W on the shoulder, white earbud wires striping her hair. Silent and peaceful, even though she has such a big weekend ahead.

“Go Washtenaw Pride,” Mikey whispers, smiling.

With a finger she swabs a tear from an eye. She pictures her father in the bleachers, screaming, GOOOOO PRIIIIIIDE! again and again, regardless of whether Bridget’s team was ahead or behind. How happy it would have made him to be in the stands this weekend, narrating the game like a play-by-play announcer for Ophelia, who is blind. “G-Pa will be rooting for you from heaven,” Mikey told Bridget as they packed her sticks and hockey bag into the car.

The weekend will be good. Mikey is sure of that. Whatever happens on the rink, win or lose, skate well or not, will happen. There will be time with Ophelia, time with Ophelia’s boyfriend, the smell of the house on Bleak Harbor Bay that will bring Bob Wright back to life, if only in their minds. And there will be time with Bridget, often so hard to snatch at home between school and work and practice and games.

Mikey’s phone buzzes. Craig calling.

“Hey,” she whispers.

“Everything OK?”

“Heading to Pheels’s place. Bridget’s out.”

“Good. She’ll need her energy.”

“When are you leaving?”

“Right after this breakfast with the deans. Of course they had to schedule it for this Friday.”

“Be safe. I love you.”

“Me too.”

Mikey had an easier time getting Friday off from her job as associate director of the Richard T. Willing Literacy Center in Ann Arbor. She knows Craig would be with them if he could. Bridget’s hockey means more to him than to Mikey, maybe even more, Mikey suspects, than it does to Bridget. This weekend looms large for their daughter’s future: five games, the best girls’ teams in North America, college scouts watching.

Bridget has heard already from Wisconsin, Colgate and Darwyn Tech. She’s holding out for Harvard. Her father’s hoping for Wisconsin.

Mikey just wants her daughter to be happy. She doesn’t care what makes Bridget happy—hockey or microbiology or accounting or geography—so long as it’s something that wakes her up each day with purpose and meaning, something that won’t scare her so badly that she’ll come to the conclusion that she has to walk away. Like Mikey did.

She’s glad for a few days away from her job. She likes it, mostly, especially the one-to-ones with the kids and adults who come to learn to read. It reminds her a bit of what she loved most about being a newspaper reporter: interacting with opaque strangers who gradually become real people, almost familiar.

But since her promotion to associate director, Mikey has been spending less time with people and more with grant applications and other paperwork. Financially, the literacy center is scraping by about as badly as the Detroit Times was when she left nearly twelve years ago.

The bay road becomes Blossom Street and curves into the heart of Bleak Harbor. Lights are on at Nucci’s Nice Guy Tavern. Otherwise the street is dark but for the furry glow of faux gas lamps. In three months, it will be crowded and blazing light with vacationers from Chicago and Detroit and Indianapolis. This is March, chilly and damp with winter’s last wheezing breaths.

Mikey passes Kate’s Kakes, Strawman Drug, the pizza joint that changes names every year or two, Casurella Fudge. At the intersection of Blossom and Lily, the clock tower on the Bleak Harbor Bank & Trust building says 9:17 p.m. Mikey turns right onto Lily, which slopes downward toward the vacant harbor docks. She’s about to take a left onto Jeremiah when an SUV lurches out from a driveway on her right into the middle of the street and stops. She slams on the brakes, stopping just short of the SUV’s rear bumper, one arm instinctively reaching out to keep Bridget from pitching forward.

“What the hell, idiot?” she says. She looks at Bridget, who merely shifts her head from one side of the seat to the other, still asleep.

The SUV looks similar to the black Volvo that Ophelia keeps, but the license plate is from Ohio. Of course, Mikey thinks, because everyone in Michigan knows Ohioans can’t drive for shit. Maybe it’s carrying a girl playing in the tournament. Maybe the driver saw the Washtenaw Pride sticker on Mikey’s windshield and decided to have some fun with her.

Mikey doesn’t really care; she just wants to get to Ophelia’s. But the Ohio Volvo doesn’t move. Mikey doesn’t want to honk and wake Bridget, so she puts her car in reverse, backs up a few feet, and starts to maneuver around the Volvo on the left. Then Ohio veers in front of her and brakes again.

“Come on, jerk,” Mikey says under her breath. She backs up again, again starts to move around the SUV, and again Ohio eases forward to obstruct her. She squints to read the license plate, commits it to memory, then backs up again, faster now, and tries to squeeze past along the curb. This time Ohio doesn’t move. She looks at the car as she’s creeping past. Through the tinted side window, she sees the shadowy outline of a head turning toward her.

The window begins to slide down. Mikey looks over, expecting a middle finger. Instead she sees a man’s face—at least she thinks it’s a face, not a mask. She gasps as she swerves left and bumps up onto the curb.

“Oh my God,” she says as he stares across at her. She thinks the face might be grinning, but it’s so grotesquely deformed she can’t be sure.

Bridget bolts up, the fleece falling away.

“Don’t,” Mikey says. “Don’t look.”

Ohio speeds away.

“Mom,” Bridget says, “you scared me.” She twists to look out the passenger window. “What happened? Who was that?”

“Just some jerk, probably drunk,” Mikey says. In her head she repeats what she saw on the license plate: W19BB6. “Everything’s fine.”

“You always say that.”

“Look, we’re almost to Ophelia’s. Get ready.”

The author holds his new book and wears an image of his previous one. (Photo: Facebook)

Mikey takes a breath and swallows hard, hoping Bridget doesn’t notice her unease, then turns onto Jeremiah. The street is lined with Victorians built in the late nineteenth century, after Joseph Estes

Bleak came from New England and transformed a swamp along Lake Michigan into a small but thriving timber-and-shipping hub. She parks in front of a gray two-story trimmed in forest green and drab white.

Ophelia rents the first floor. The house is dark but for a finger of light in the bay window facing the street. Mikey doesn’t see Ophelia’s Volvo by the curb. Maybe it’s in the garage. Ophelia can’t drive it, of course, but she insists on having it because she’s Ophelia. Her business partner borrows it on occasion.

In the front yard stands a sculpture Ophelia fashioned from scrap metal and aluminum wire. A boy on a skateboard balances on one bent leg, arms flung triumphantly out to his sides, head thrown back, presumably shrieking with laughter. A word is inscribed on the top surface of the skateboard: Lucky.

Seeing it makes Mikey’s throat catch, as always, and she thinks, Zeke. You can’t get lucky if you don’t try. A larger version of the statue towers over Blue Star Highway north of Bleak Harbor, one of seven sculptures Ophelia has constructed along the road.

Bridget is shaking out her hair. “Want me to go up to the door?”

“Wait one second.” Mikey dials her sister again. Again it goes to voice mail. Ophelia is a sound sleeper. And stubborn when she wants to be left alone. “Let’s let her sleep. We’ll see her in the morning.”

As they circle back through the lifeless downtown, Mikey keeps a lookout for Ohio. Did the face in the window actually have only one eye? She makes a note to look for him at the rink tomorrow.

“Look at the bay,” she tells Bridget. “Isn’t it beautiful?”

The water is a black mirror, stars reflected as pinprick glimmers on the glass, stretching from the beaches along the bay road to the far shore, where the old Bleak Mansion squats atop a sandy slope peering down on the city. Seeing the house with its peaked roof and pink turrets as a young girl always gave Mikey a little thrill, like she was glimpsing one of the castles she’d read about in picture books. One day, she used to think, she’d write about her own castles.

“Does anyone live there anymore?” Bridget says.

“I don’t think so. The old lady died a while back. The property’s all tangled up in lawsuits.”

“That’s sad.”

“Who’s this?” Mikey’s Bluetooth is ringing. “Gary?”

“Hey there,” Ophelia’s boyfriend says. “Welcome back.”

“Thanks.”

“Hi, Gary,” Bridget chimes in.

“Hello, hockey goddess. Can’t wait to meet you.”

“Is Ophelia with you?” Mikey says.

“Nope. I tried to get her out for dinner, but she begged off, said she had work to do and wanted to get some sleep before the big weekend.”

Mikey encountered Gary Langreth once years before, when she was a night-police reporter in Detroit. He was in a briefing with the department’s communications officer after a triple shooting on the East Side, sulking about having to deal with a reporter and giving her just about nothing. He somehow remembered it years later when they met in Bleak Harbor, maybe because Mikey was the rare woman covering night cops. “Props to you for handling assholes like me,” he told her.

After Ophelia started dating him, Mikey Googled him and saw that he’d left the force a few years ago and come to Bleak Harbor to work as an investigator for the county prosecutor. What had prompted his departure from Detroit was unclear; veteran detectives didn’t often abandon their pensions.

“She’s not answering her phone.”

“Yeah, well, you know what she thinks of phones.”

“The phone is a privilege,” Ophelia liked to say. “You have to ignore it sometimes to keep its specialness in perspective.”

“You’re staying at Bob’s?” Gary asks.

“Yeah, more room there, and there’s still some of his stuff to go through.” Her father kept the house on Bleak Harbor Bay after he went into assisted living two years ago. She and Ophelia have been trying half-heartedly to sell it ever since. “Bridget likes to sleep in G-Pa’s bed.”

“I wouldn’t worry about Ophelia. She probably conked out. She’s very excited about the tournament. And of course it’s her birthday.”

Zeke’s birthday too, Mikey thinks. “Of course,” she says. “So we’re having breakfast at Bella’s? Eight?”

“Eight? Ugh,” Bridget says.

“When’s the first game?” Gary says.

“Eleven forty-five.”

“See you at Bella’s.”

Mikey brakes and flicks her left-turn blinker. “Here we are.”

She pulls into a gravel horseshoe drive in front of a one-story clapboard house with an attached garage. There must be ten thousand cottages like this one on lakeshores all over Michigan. That’s why her father loved it so much. Before he moved the family there, when they were just weekending, Bob Wright would roll up to the house, toss his bag on the kitchen table, pop a cold can of Stroh’s, and go directly out to the water, the screen door banging behind him as he took his first guzzle.

He called it prioritizing.

Now a For Sale sign juts from a row of scraggly evergreen shrubs beneath the kitchen window. The sign is listing a little, as if it doesn’t want to be there any more than Mikey wants it there.

“Hmm,” she says.

“Ophelia was supposed to stop by and put a light on. So the furnace probably isn’t on either.”

“That’s sad too,” Bridget says.

“It’ll heat up quickly enough.”

“No, I meant the For Sale sign.”

Neither Mikey nor her sister wants to sell it. But their father, in his late-life state, neglected to pay property taxes on the house for almost two years. Keeping it would be a costly hassle. “Yeah. We haven’t had any bites, so maybe we’ll hang on to it for the summer at least.”

“I wish G-Pa was here.”

Bridget opens her door, but Mikey stops her with a hand on her knee. “Everything is going to be great this weekend, Bridge.”

“Stop saying that.”

She tries to get out, but Mikey squeezes her knee harder and says, “I want you to have fun. Have fun.”

Bridget stares at the glove box. “I can’t get a scholarship having fun.”

Hearing that breaks Mikey’s heart a little. She wants to ask Bridget, Aren’t you having fun? It isn’t fun to be out there on the ice with your friends? But Mikey is afraid to hear the answer.

Instead she says, “You’ll feel better when all this college stuff is over, honey. Promise.”

“What was that in that car?”

I don’t know, Mikey thinks, struck by Bridget’s choice of pronouns.

What describes that face better than who.

“Just some Ohio jerk,” Mikey says. “Oh, wait, that’s redundant.”

Bridget smiles a little. Mikey, feeling glad, releases her daughter’s knee and says, “Let’s get you to bed.”

Text copyright © 2020 by Bryan Gruley. All rights reserved.

About the book

- Formats: Hardcover (332 pages), paperback, digital and CD

- Release: Jan. 14 (available for preorder)

- Review: “A fiendish quest for revenge drives Gruley’s tense thriller.” – Publisher’s Weekly

- Amazon: $14.95 hardback, $11.99 paper, $4.99 Kindle, $24.99 CD

- Barnes & Noble: $17.47 hardback, $11.99 paper, $24.99 CD

- Author visit: Jan. 17, 7 p.m., My Little Paris Café & Bookstore, 141 E. Main St., Northville.