A few weeks ago, around the same time the Free Press was announcing its now-expected end-of-year staff reductions, which had four Freep veterans taking buyouts to spare their colleagues layoffs, something else of note happened in journalism: The Orange County Weekly folded, with little notice.

The California publication had been struggling; it had already lost one editor-in-chief who refused to cut staff. And in closing shop, it joined an expanding graveyard of similar publications, alt-weeklies that for years had served as a vital voice in any number of cities’ civic landscapes. It was a reminder that the degradation of print media has not been limited to dailies like the Detroit News and Free Press, although they have gotten the lion’s share of attention.

All this by way of asking: How’s Metro Times doing?

The short answer: Not bad. Not terrible, anyway. Wounded by the digital destruction of print media? Absolutely. The staff is smaller, the paper thinner than in years past. Its ownership is based in Cleveland, not Detroit. But it’s still publishing, thanks at least in part to advertisers who can’t really go anywhere else to reach a general, local audience – strip clubs, marijuana dispensaries and even sex workers. Hence the alt, i.e., alternative.

The longer answer is more complicated, reflecting the high-wire act that publishing is at this moment. It's a scramble to keep a media business afloat, balancing the maintenance of journalistic integrity while dealing with possible revenue loss by offending advertisers. For these smaller, scrappier papers, advertising isn't the easy money it used to be, and actually, it isn't that way for any publication. Margins are leaner and the cliff, closer.

Metro Times publisher Chris Keating (Photo: Nancy Derringer)

Weekly circulation is in the 40,000 range, publisher Chris Keating says. Visits to the website are “ridiculous,” in a good way – over 1 million page views a week. The company has diversified into events and marketing, further insulating itself from at least some of the revenue storms buffeting print media.

At the same time, when local columnist Jack Lessenberry quit in a #MeToo controversy in May 2018, he was replaced by a syndicated writer based in North Carolina, meaning the number of columns about Detroit issues that once appeared in that space dropped to zero. There has been talk MT has gone soft, from time to time, on the Ilitches, for fear of losing the significant ad dollars Olympia Entertainment controls. And there’s the simple matter that fewer writers are covering the city and producing the sorts of stories that keep readers coming back.

Birth of an outsider

It’s hard to be a newspaper dedicated to sticking it to the man, man.

That man is necessary to understand alt-weeklies, the DNA of which evolved in the 1960s. So-called “underground” papers were often produced by amateurs who covered what they wanted, free of the strictures imposed on traditional media sources.

Harvey Ovshinsky was 17 when he founded The Fifth Estate in Detroit in 1965. His mother had just relocated him to Los Angeles, to start fresh with her new husband. Her son was miserable, but while he was there, he discovered the L.A. Free Press. When he found his way back to Detroit the following year, he wanted to “share what I’d learned in L.A.,” he said.

What he’d learned was pretty vague, only that “there was something going on here but I didn’t know what it was.”

Like dozens of other free weeklies founded around that time, Ovshinsky made it up as he went. He covered peace groups and their activities. He published record reviews. Advertising came from businesses too small to afford what the dailies were charging for ad space, but who knew their customers and what they were reading. In time, the younger members of The News and Free Press staff would read it, if only to know what was going on in places their own papers weren’t covering.

“(The editors of the dailies) didn’t understand their children, let alone the alternative media,” Ovshinsky said.

No shortage of men to stick it to

The Fifth Estate still exists, in a very different form, as an anarchist quarterly. But its story is the origin story of the alternative press, and you can see its influence on the Metro Times, founded far more recently, in 1980.

It still seeks to zig when other publications zag, to cover stories the dailies don’t. In 2017, when the dailies were writing upbeat stories about the great new hockey arena opening downtown, MT dropped three distinctly non-effusive ones – one on a struggle over historic buildings in the Little Caesars Arena district; another accusing the Ilitch family of “dereliction by design,” a long-term strategy of neglecting a neighborhood to drive down property values; and a story by its music writer, Jerilyn Jordan, on the experience of attending all six of the Kid Rock shows that kicked off Little Caesars as a music venue. In keeping with her oft-expressed opinion that Kid Rock is terrible (“the musical equivalent of a DUI with all the charm of a human cigarette”), it was not exactly a kiss on the cheek:

“Is this how James Franco's character felt in that movie ‘127 Hours?’ Cutting my own arm off would do no good here…”

These pieces were in the stick-it-to-the-man tradition, and they cost the paper advertising, said editor Lee DeVito. MT’s coverage of the Ilitch organization has been mostly in this vein, and to be sure, the broken promises of the Ilitches’ District Detroit is classic alt-weekly news fodder.

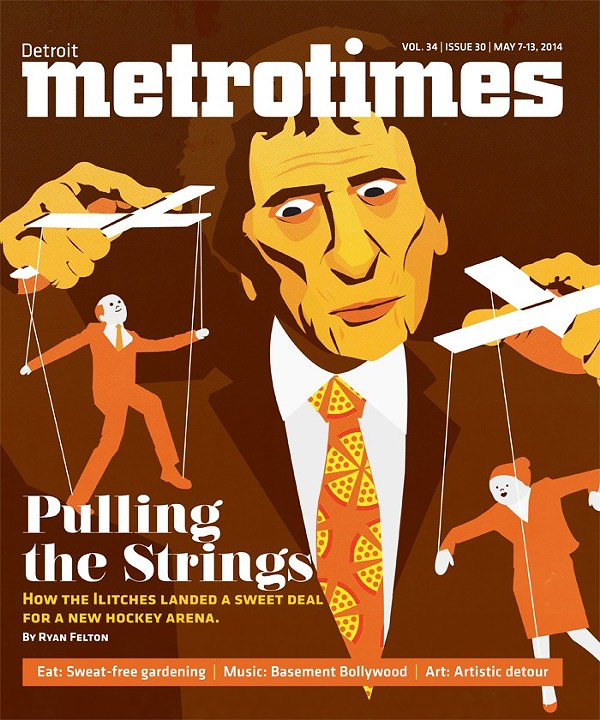

No bigger man to stick it to: The Metro Times' cover on the LCA deal

In 2014, then-staff writer Ryan Felton wrote a critical cover story about the arena deal, complete with a cover illustration depicting the late Mike Ilitch – toying with marionettes, presumably Detroit politicians – as the “string-pulling” manipulator who worked out a deal that built the billionaire family their new arena with hundreds of millions in public dollars. It was exactly the sort of story readers should expect from their alt-weekly, but a perilous one, too.

The arena is not only for hockey and basketball. It also hosts concerts and stage events. The Ilitches also own the Motor City Casino and the Fox Theater, with their own entertainment spaces. And all of which advertise as Olympia Entertainment.

But when Tom Perkins, then a Metro Times staff writer, wrote an accusatory story in October 2018 about the failure of the Ilitches to deliver on the District Detroit, it appeared in The Guardian, a European newspaper and website based in London.

It was an important piece, a leader in a swiftly turning tide of Ilitch coverage. (Deadline contributed its own stories.) HBO Sports aired a similar segment a few months later. Soon The News and Free Press and Crain’s Detroit Business were pointing out the obvious: Once again, the Ilitches had overpromised and under-delivered (or never delivered) on a self-enriching project, while the public foots much of the bill.

DeVito’s response to why Perkins’ piece ran in the Guardian?

“Sometimes something like that has more impact when it comes from outside,” he said, a curious response for an editor whose own writer had deprived him of a story that changed the conversation.

The omission led to media-community talk that Metro Times had backed off the Ilitches for fear of losing significant ad dollars. DeVito denies this.

“I don’t want to create a feeling like we were piling on,” he said. “We were never going to not cover them, but we were never only printing negative things.”

Even if the Ilitch organization was receiving kinder treatment from Metro Times, it would hardly have made much difference, he added; the Ilitch organization never responded to the paper’s requests for comment on other stories. “But they fucking dumped Kid Rock! I feel a little vindicated.”

Perkins no longer is on Metro Times’ staff, although he still contributes. When asked why he sold the story as a freelancer to the Guardian and not to his employer, he did not answer directly, but responded in an email:

"The context in all of this worth highlighting. Metro Times published dozens of stories since 2012 that hit the Ilitches hard over the arena deal, failure to follow through with their promises, and their shady business practices. No other local outlet seriously or consistently questioned the family until 2018. Most reporters/editors in the Detroit media didn't see what was happening or were afraid of the Ilitches. Either way, they failed to do their jobs."

Francis Grunow is a neighborhood and preservation activist, and former chairman of the Neighborhood Advisory Committee, formed as part of the arena project. He said he considers the paper “definitely an ally” in holding the powerful accountable in the District Detroit issue.

The paper, he said, has had “eras of ownership” and shifting editorial vision, exacerbated by staff turnover.

But, Grunow added, “I feel like they’ve done a good job in terms of covering and uncovering (the District Detroit story). They’re putting good brains and ink on the story.”

Metro Times management has shown in the past that it can be intimidated. In 2015, Felton wrote a critical piece about the businesses of another Detroit billionaire, Dan Gilbert, raising questions about Quicken Loans' role in last decade's mortgage crisis. Gilbert's empire is prickly about unflattering media coverage, and raised objections to MT management. Keating's response then was to take Felton's story down -- "unpublishing" it -- for a few days, while it underwent an "internal review." The story was eventually republished with what the then-editor called a "minor deletion."

But the act of actually taking a story off the site is a radical one.

"Digitally 'unpublishing' a story, even temporarily, is a step that should not be taken lightly, and never without a clear explanation to readers," wrote Anna Clark in Columbia Journalism Review at the time, noting that Keating told her it "happens periodically" at Euclid Media publications.

Turbulence in the top job

DeVito may seem an unlikely choice for editor in chief. After a long period under the stewardship of W. Kim Heron – who was either managing editor or in the top job for 13 years, ending in 2012 – the Metro Times blew through three editors, all of whom served for less than a year, which Keating attributes to having “great writers” in the job, but “being a manager and leading a team is a different skill set.” DeVito, hired in November 2016, is a visual artist and graduate of the College of Creative Studies, whose journalism experience was mainly in contributing record reviews to the publication he now leads.

His application for the top job was basically a fan letter, he admits, telling the publishers at Euclid Media how important the paper was to him as a teenager growing up in Farmington, a window into what was going on in the arts-and-culture scene. And it was “unapologetically left” politically, which he also liked.

But his hiring, he said, is of a piece with the alt-weekly tradition, where outsiders are celebrated, not stifled.

“We don’t have to shackle ourselves to that neutral-observer thing,” DeVito said. “We can have a point of view. We’re punching up, not down.”

He’s right about that tradition. Some of the most respected journalists in the U.S. made their way to the top via the alt-weekly lane, and not all were J-school grads; Jake Tapper, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Susan Orlean, Dan Savage, Lindy West, Eric Wemple and the late David Carr are among them, whose work now appears in outlets ranging from The Atlantic to The New Yorker to the New York Times, Washington Post and various best-sellers.

Metro Times editor Lee DeVito (Photo: Nancy Derringer)

Today, DeVito said he is learning journalism on the job, and relies heavily on his far more traditionally experienced staff and key contributors, who include Motor City Muckraker Steve Neavling, Perkins, Michael Jackman and others. (Deadline Detroit’s Violet Ikonomova worked there nearly two years until her hiring here in November 2018.) But there are only four full-time staffers on the editorial, or content-producing side, fewer than half of what it had 10 or 15 years ago.

“I don’t read it as religiously as I used to,” said Heron, who now works in communications for the Kresge Foundation. “They’re still doing good stuff, though.”

Heron sees the role of the Metro Times as “complementary” to the dailies and mainstream media, rather than antagonistic. But at its core it remains the same publication he led through the late ‘90s and early 2000s, he said, one that “(takes) culture seriously and puts it on a par with news.”

Metro Times wrote some of the first stories about the White Stripes and the rise of techno, Heron said. Being able to put a culture story on the cover every few weeks could give those stories more prominence than if they were buried inside a daily newspaper, even if the latter’s circulation was far greater.

And give it this: In a review of Magnet, a super-hot new restaurant in the Core City neighborhood, critic Jane Slaughter led not with a rapturous description of the fire-kissed broccoli, but a question about whether “anyone living within a quarter mile could afford to eat here” and went on to observe:

When the cheapest way to order is the Chef's Selection at $60 a head, and yet the owners call the place "a simple new restaurant," there's a disconnect. Press materials say "Magnet is reminiscent of an era before grand tales of Detroit's comeback," but the opposite is true: if any restaurant is more emblematic of this decade's gentrification, I have yet to visit it.

Diversification and less confrontation

Publisher Keating says he respects the so-called “Chinese wall,” journalese for the separation between advertising and editorial that legitimate media purport to have. And the business side is a full-time job for anyone.

“Our company is a media company, a digital marketing company, and an event company,” said Keating, pointing to side projects like Pig & Whiskey in Ferndale and the Metro Times Blowout, returning to Royal Oak this year.

At the same time, he echoes DeVito’s comment that trashing local businesses should not be a mission: “I’d never want to crater a local restaurant.” (The review of Magnet that followed that opening salvo was positive.)

(Something that should be explained for non-journalists: The tradition of editors fearing no advertiser threat was born at a time when newspapers and TV stations were fat with double-digit profit margins, the only game in town for advertising, and could afford to lose one or two without suffering any ill effects. While no publication would ever admit to bowing to financial pressure, it certainly happens more often in this leaner era with certain publications. Ask yourself why consumer-advocacy features on local TV so often target a small-time grifter and not, say, a major car dealer. All that said, it's still considered a journalistic sin to ignore stories to please advertisers.)

Keating wouldn’t speculate why Euclid Media has been successful and other alt-weekly publishers have thrown in the towel, with the latter group including some of the most venerable names in the market, the Village Voice and Boston Phoenix among them. Owners have varying strategies, he said, but Euclid has been able to pick up weeklies in Cincinnati, St. Louis and Tampa, “one of the few companies that has actually acquired more properties than shed them,” he said.

Sacred cows?

On the editorial side, life goes on as it has mostly gone at MT. Perkins broke the Founders Brewing story last fall, about a racial-discrimination lawsuit that went haywire when a supervisor stated in a deposition that he couldn’t say whether the employee even was African-American (“I don’t know his DNA”), and for that matter, he didn’t know whether Barack Obama was, either (“I’ve never met” him). Neavling was in front of the vaping-deaths story around the same time.

The paper is past the time when it landed in Columbia Journalism Review for running “sponsored content,” i.e., puff pieces about advertisers without clearly labeling them as such. That, Keating said, was a result of Metro Times merging with Real Detroit Weekly, which was far more open to such arrangements. But the publisher who approved those arrangements is gone now, Keating said, and today a few stories-plus-ads issues (Best of Detroit and the Movement preview, most notably) are labeled as such and in the vein of coverage the paper does anyway.

The syndicated columnist who replaced Lessenberry, Jeff Billman, is editor of Indy Week, in Durham, N.C. He's also editorial chair of the Association of Alternative Newsmedia, the niche's industry group. Billman is philosophical about alt weeklies, including the one he edits.

"Everything is changing all the time," he said. "It's like any other form of print media. We're trying as an industry to shift and figure out what can work and what doesn't."

It's clear to Billman that "business models will have to change." Consolidation might work. Diversification might work. A public-radio model of reader support might work, at least a little. But in the great alt-weekly tradition of throwing the map out the window, that's what lots of publishers are doing, he said:

"The trick is to figure out what we’ll be doing five or 10 years from now."

by

by